Secondhand Trauma is Still Trauma

Growing Up in the Shadow: Second-Generation Effects of Alcoholic Homes

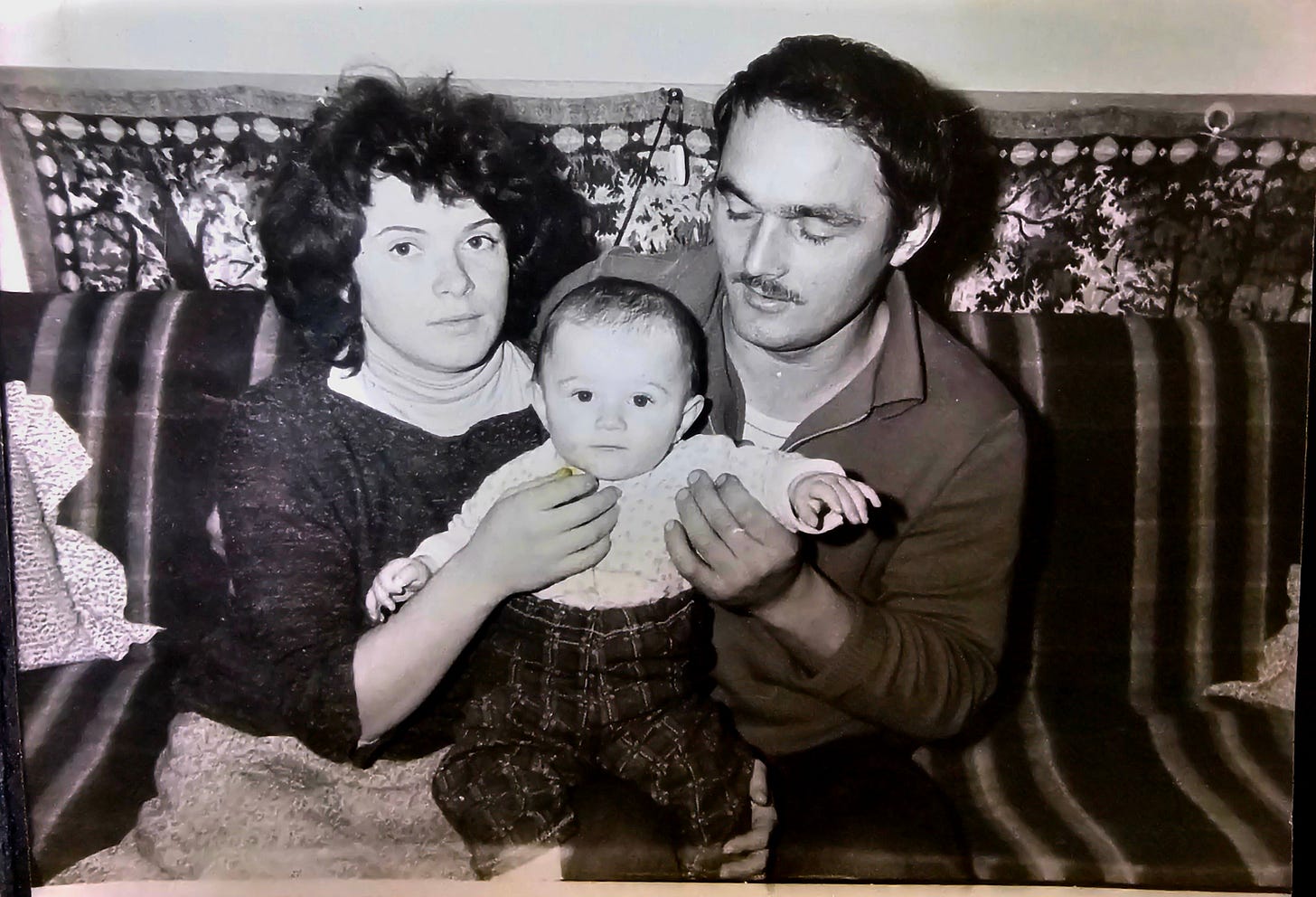

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how the past finds its way into the present… how pain that isn’t ours can still settle into our lives like something inherited.

My mom grew up in a deeply traumatic home shaped by alcoholism and violence. Her father, my grandfather, was an alcoholic, often drunk, often enraged.

There were beatings.

There was screaming.

My mom, as a child, was told to be seen but not heard.

If she dared speak up, she was silenced harshly. Sometimes, she was left outside alone at a young age. And then there’s the story of the bull: she was only around 13 when she was nearly killed after being forced into a dangerous situation with a raging animal, only to be beaten afterward for not stopping it.

This was her childhood. This was her normal.

To her credit, my mom tried hard to raise my sister and me differently. There was no physical abuse in our home. No drinking. My dad wasn’t an alcoholic. But there was yelling, especially on Sundays, which became cleaning days. There were also loud, painful arguments between my parents. And while my mom worked hard to shield us from what she endured, we still grew up carrying the weight of something unspoken.

Now, as an adult, I see pieces of that past surfacing in me and my sister. We both struggle with speaking up for ourselves, but we do it in opposite ways. I either freeze or explode when I’m faced with confrontation. I hate both of those reactions. Neither feels like me, and both feel like echoes of something older, deeper, and unfinished.

This has made me wonder: What happens in second-generation alcoholic families? What are the patterns, the wounds, the invisible threads we may not even realize are there?

Secondhand Trauma Is Still Trauma

Even though my childhood didn’t involve alcohol or violence directly, I grew up with the residual effects of trauma. This is often referred to as "secondhand trauma" or intergenerational trauma. Children of alcoholics, and even their children, often live with unspoken emotional patterns shaped by survival.

Here are some of the common struggles seen in second-generation families of alcoholics:

1. Hypervigilance

Children raised in unpredictable, emotionally intense homes often grow up constantly scanning for danger, even in calm environments. That sense of "waiting for the other shoe to drop" can become internalized, even when there’s no immediate threat.

2. Conflict Avoidance or Explosive Reactions

Because we didn’t grow up seeing healthy conflict, we may swing to extremes. Some of us avoid confrontation entirely (freezing, shutting down), while others overreact (yelling, emotional flooding). Both responses often stem from not knowing what safe conflict even looks like.

3. Difficulty Expressing Needs or Setting Boundaries

If you were told to "shut up" or "not complain," you might now feel guilt or fear when asserting your needs. You may struggle to draw boundaries or feel selfish for protecting your energy.

4. People-Pleasing and Perfectionism

Trying to avoid criticism or punishment might lead you to overachieve, be overly responsible, or say “yes” when you mean “no.” You become the peacemaker, even at your own expense.

5. Emotional Suppression

Feelings like anger, sadness, or fear may feel dangerous to express. You might suppress emotions until they build up and come out sideways, maybe in outbursts, shutdowns, or physical symptoms like anxiety or fatigue.

6. Impaired Self-Worth

Growing up feeling invisible, or only receiving attention when something was wrong, can leave you doubting your worth. This can show up in relationships, work, and self-talk.

Healing Is Possible

The pain from our parents’ or grandparents’ homes doesn’t have to define us, but it does need to be acknowledged. Healing starts with recognizing that just because we weren’t directly abused or neglected doesn’t mean we weren’t impacted. It’s okay to grieve the emotional tone of your upbringing. It’s okay to say, “This shaped me in ways I’m still trying to understand.”

Therapy can help, especially trauma-informed or intergenerational work. Journaling, inner child work, and open conversations with siblings or trusted friends can also be powerful. Sometimes, just naming the pattern is a breakthrough.

What I’ve come to realize is this: my mom survived something that no child should have had to. She did her best to break the cycle, and in many ways, she did. But cycles are tricky. They can shift shapes. They can linger in silence. And they don’t truly end until we face them head-on.

I’m learning to be patient with myself as I sort through what’s mine to carry and what isn’t. While sometimes frustrating, I’m learning that my reactions make sense when I trace them back to where they started.

I don’t want to freeze or blow up when I’m scared. I want to respond, not react. I want to break the cycle, not just survive it.

And maybe, little by little, that’s exactly what healing looks like.